Beliefs and Definitions of pain

Historically, humans have been very interested in the pain experience and have had a wide variety of explanations regarding pain.

In Ancient Greece 500 BC they believed that pain occurred when the Goddess of revenge, “Poine” was sent to punish fools who had angered the gods. Treating pain involved prayer and animal sacrifice.

Many ancient cultures believed that pain was something inside the person which had become stuck and needed removal.

Holes were drilled into body parts and sometimes pipes were used to “suck the pain out”.

During the 1600s there were giant leaps in scientific understanding.

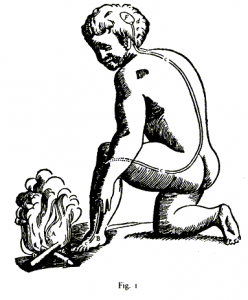

Rene Descartes proposed the idea that pain was a mechanical sensation transmitted to the brain. The body part that had been injured sent a message up to the brain where it could be received and understood as pain. In order to treat the pain either the injured body part needed to be fixed or the message needed to be stopped.

We have largely held onto this understanding of pain into current times. We only need to watch advertisements for commonly used painkillers to see images involving pain being transmitted from the injury to the brain and then the painkiller smashing away the transmission to stop the message before getting to the brain. Research has clearly shown that pain is far more complicated than this, through studies of people with phantom limb pain after amputation and a variety of other examples that clearly demonstrate that pain actually does not correlate well with degree of injury.

So what then is pain? There have been many attempts at defining pain.

Some of the more useful ones include:

“Pain is whatever the person in pain says it is.” – McCafferey (a nurse) 1968

“Pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage.” – The International Association for the Study of Pain (1994) and the World Health Organisation (2007)

“Pain is a construction in the brain to help us deal with threat, either real or perceived via a change in behaviour.” – Mature organism Model, Gifford (1998)

“Pain is a multiple system output activated by an individual specific pain neurosignature; the neurosignature is activated whenever the brain concludes that the body tissues are in danger and action is required.” – Lorimer Moseley (2003)

These more recent explanations of pain focus on threat and danger; pain is explained as a mechanism produced by the brain to protect us from harm. Physical harm (e.g. accidentally putting your hand onto the hotplate) is reasonably easy to understand. The combination of nociception (the activation of physical receptors to physical changes such as pressure, temperature and chemical change) as well as the visual perception of danger causes the brain to produce a pain response. This causes the physical response of quickly moving your hand away from the hotplate and perhaps running it under cold water. The pain response is not only caused by the physical stimulus of heat, but also by our awareness that leaving our hand on the hotplate could potentially lead to a severe burn (that is, our perception that the situation is potentially dangerous).

However, pain can occur in a variety of situations where there is no physical damage.

One example of this was documented in the British Medical journal in 1995. A builder jumped down onto a nail in a building site, which went right through his foot and was sticking out through the top of his shoe. Understandably, the man was screaming in considerable pain. He would not allow anyone to remove his shoe as the slightest movement caused extreme pain. He required sedation and strong pain medication to enable him to be x-rayed (with the shoe still on), to discover that the nail had actually gone straight between his toes and had not penetrated his foot at all – not even a scratch!

It may be easy to think that this pain is somehow not “real” as there was no damage. However, his pain is equally as real as if the nail had indeed gone right through his foot. In this case the visual perception, combined with previous experience involving serious injuries on the worksite was enough to cause the brain to decide the situation was extremely dangerous and that pain was required to ensure the danger could be resolved.

In other examples, people have had horrendous injuries and not experienced much, if any pain.

In 2010 Jonathan Metz had been trapped in his basement for approximately three days with his arm stuck in the furnace and little chance of being found chose to saw off his own arm in order to escape, and survive. After the traumatic incident explained his surprise at not experiencing much, if any pain through the process. He certainly expected it to hurt and felt physically sick looking at what he was doing, however only mild pain was felt. This can easily be explained through this threat model of pain, as his brain had come to the conclusion that the threat of being locked in the basement was far more dangerous than the threat of cutting off his arm. In the absence of a perception of danger involved, no pain needed to be produced. There are many similar examples in the area of sport, where athletes feel little or no pain during or immediately after a severe physical injury.

Important things we now know about pain

- No scan or test can tell if someone is feeling pain or not. X-rays, CT scans and MRI results have been consistently demonstrated to be very poorly correlated with the experience of pain.

- No one else can feel your pain

- ALL pain is real

- You cannot imagine pain

- Pain can be weird (e.g. delayed pain, phantom limb pain, pain that spreads to unrelated areas)

- Nociceptive nerve fibres are triggered by chemical change (e.g. inflammation), physical events (e.g. pressure), and temperature changes

- Nociceptive nerve fibres can adapt and amplify their signals through frequent triggering, generally leading to increased pain with reduced activity levels

- Pain is influenced (positively and negatively) by mood, concerns, thoughts, perception of control, importance placed on the injury, and a range of other cognitions.

- Pain can be influenced by boom/bust behaviour and flare ups

So what does this all mean?

Pain is useful and should not be ignored. Pain is a protective mechanism generated by the brain in response to perceived threat. However, when pain is persistent and there is no direct or immediate threat to the body, understanding how the body can get “stuck” in pain can suggest ways to help it get “unstuck.”

All current evidence leads to the conclusion that PAIN IS CHANGEABLE!

Pain is produced by the brain and we also know that the brain is constantly going through changes. Neuroplasticity can be defined as the brain’s ability to reorganise itself by forming new neural connections throughout life. Neuroplasticity allows the neurons (nerve cells) in the brain to compensate for injury and disease and to adjust their activities in response to new situations or to changes in their environment. Examples of this include learning a new skill, developing a taste for certain types of food and recovering from stroke. Dr Norman Doidge, A psychiatrist and researcher from the University of Toronto in Canada has highlighted the importance of neuroplasticity for healing a range of conditions from long term pain to Parkinson’s disease in his bestseller The Brain That Changes Itself (2007).

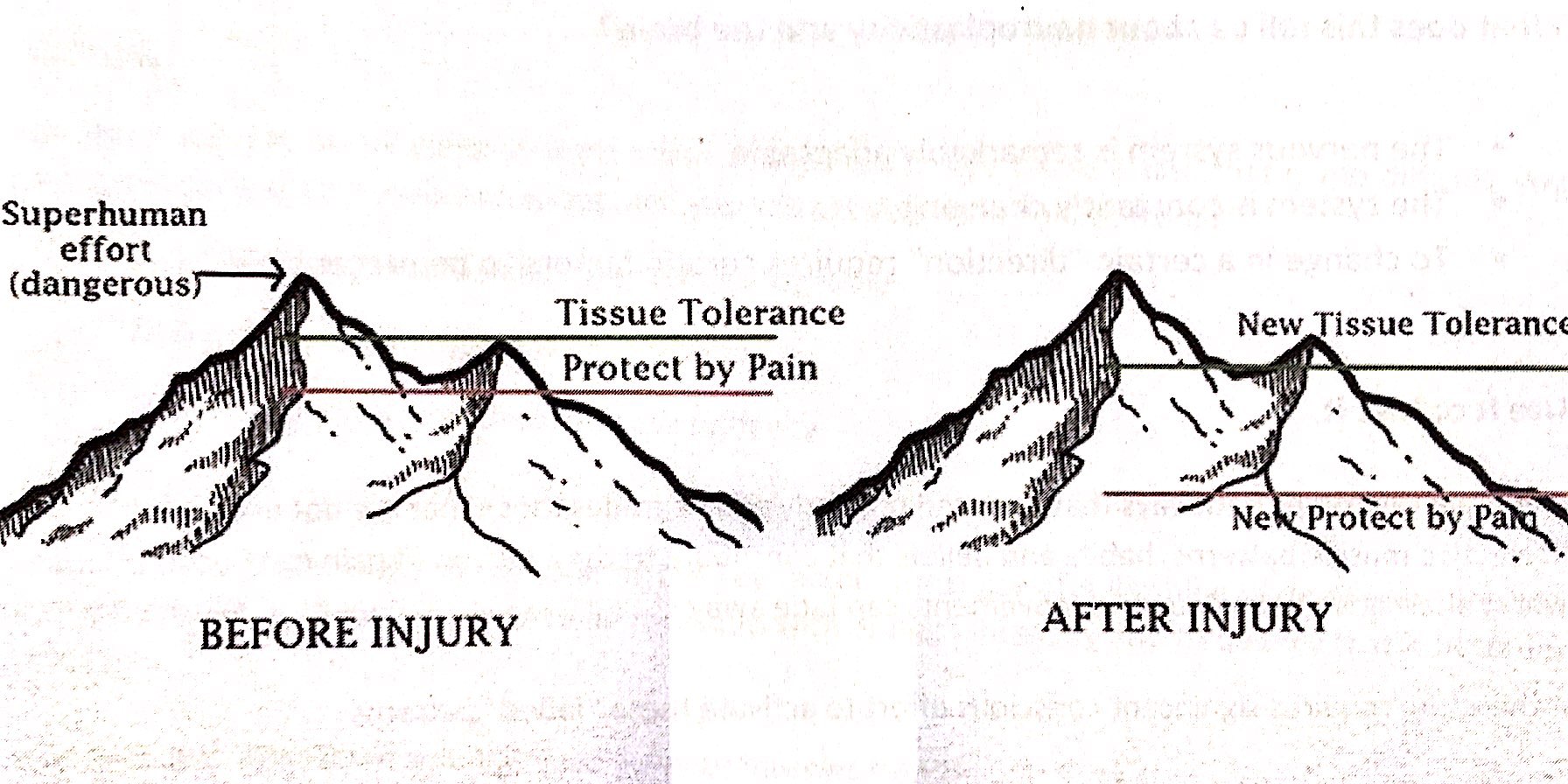

Everyone has a tissue tolerance level, that is a threshold where activities go from being safe to being dangerous. This differs between individuals and can also change over time through inactivity, exercise, strength training etc. When pain is working effectively, the protect by pain line sits under the tissue tolerance level so that as we begin to approach our tissue tolerance threshold, pain kicks in to remind us to stop or slow down or at least let us know we are reaching our limits. After an injury, the tissue tolerance level may slightly reduce as newly healed structures may not be quite as strong or capable as before. Most healing will be complete after 6 weeks (often much sooner, depending on the injury) meaning it is safe to go back to physical activity. However, in persistent pain problems, the protect by pain level has significantly dropped, so that even the slightest activity can be enough to set off the pain signal.

The key point to focus on is that these changes have primarily happened within the brain and the brain can be retrained. This retraining allows the protect by pain line to slowly and steadily increase until it is once again sitting just under the new tissue tolerance line. This is done through pain education and gradual exposure to safe activities through a pacing program. It is important that people know that even though it may hurt, the activity is safe. Building up slowly increases confidence and decreases the fear and threat of danger. The new tissue tolerance line can also be changed through safe exercise and strengthening activities. People do not have to suffer ongoing pain indefinitely.

At Adaptive Workplace Solutions we can provide pain education combined with meaningful goal setting and pacing/graded exposure plans to assist people with ongoing pain problems get back to everyday activities for work, play and life! If you would like further information please contact us to talk to one of our consultants in more detail. For further reading, we highly recommend the book Explain Pain by Dr David Butler and Dr Lorimer Moseley.