If you are thinking “awesome, I finally have the perfect ergonomic position at my workstation; my eyes line up with the top of the monitor, I’ve got my lumbar support chair, my hips are at a comfortable 90 degrees, my feet are propped up to the exact right height, now I mustn’t budge from this position,” then you may need to adjust priorities.

Something we emphasise with our office-worker clients is that while ergonomic set-up is certainly helpful, the most important tool to prevent sedentary work injury is to move. Often that stiffness in your neck or back when you wake up in the morning isn’t because you slept wrong, or your desk isn’t set up right, it is most likely because you did not move enough the previous day.

Here are some tips to fit movement into your day:

- Set a timer for every 15 minutes to do some sort of movement (you can cycle between quick neck stretches, a few sit-to-stand movements, walking… listen to your body)

- Many people have trouble doing the above as they want to “get stuck into” a task for a longer period without distractions. This is fine, instead you can compensate by taking longer movement breaks when you finish tasks.

- Another alternative to a timer is connecting movement to daily habits that you have already developed such as getting a coffee, going to the bathroom, or collecting printing. Every time you do one of these habitual tasks, let that be a reminder to do a quick movement for instance:

- 10 squats

- 20 heel raises

- 15 wall push-ups

- Walk up and down a staircase

- Have a small cup of drinking water so that you need to walk to fill it up frequently

- Choose to use a bathroom that is the furthest from your desk

- Use the stairs whenever you can

- If you have a sit to stand desk, change from sitting to standing (or vice versa) every hour

- Take standing/walking meetings

- Give your colleague a message in person rather than sending an email

- See our Facebook page for some simple stretches to break up your day

- Smart watches have great apps to remind you to move

- Go for a walk at lunch time – even 5 minutes makes a difference!

It will take time to develop these habits. Try adding one or two of these movements to your day, and when they have become habitual, then you can try adding more. Time should not be a barrier to beginning a movement habit, once these become integrated into your day you should find that you will become more alert and efficient in your other tasks.

Now that the risk of Covid-19 has reduced dramatically in South Australia, Adaptive Workplace Solutions have resumed face to face appointments with clients.

However, we are still taking the threat of coronavirus extremely seriously and have made a range of changes to our practices to ensure the ongoing safety and protection of our clients and staff.

Steps we have taken to ensure safety of all parties include:

- Complying with 4 square metre rule – only one person per 4 square metres of each room/building. We have calculated the square metres of each meeting room and have put up signage to ensure that we do not exceed this limit.

- Social distancing – tables and desks have been moved in each meeting room to ensure that clients and staff do not sit closer than 1.5 metres during appointments.

- Hand sanitising stations – we have purchased high quality hand sanitiser that is readily available in all of our offices for clients and staff members to use regularly.

- Disinfecting of office spaces – tables, chairs, computer equipment, benches, doorhandles, etc are wiped down with high grade disinfectant between each client. Staff are restricted to using one work area per day, with the area thoroughly cleaned each afternoon/morning.

- Contact tracing – we are collecting details from each client who visits our offices that can be used to inform the relevant health authorities in the unlikely event of a covid-19 case on our premises.

- Information provided to clients and staff – we have collected information from SA Health and from the Australian Government and are providing this to clients on arrival. Information is also displayed via posters on the walls of our offices and buildings. A clear Covid-19 safety plan has been drafted for staff and is under continual review as new advice is provided by the Government.

- Staff are instructed not to attend the office if they have any cold/flu or respiratory symptoms and clients are contacted the day before their appointment to remind them not to attend if they have any relevant symptoms. In the event that either the consultant or the client have symptoms, their appointment will be changed to a phone or video appointment.

- We are still offering telehealth appointments via Zoom video or phone for clients that are not comfortable to attend face to face appointments at this stage. We are also doing group meetings such as case conferences or medical reviews via telehealth to ensure the social distancing requirements are met.

If you have any questions about the safety of attending appointments in our offices, or would like to discuss our approach to the Covid-19 pandemic, please don’t hesitate to contact one of our friendly staff members.

What do I need to know about sleep?

Sleep is a natural process that allows the brain and body to rest and recover. When you are asleep, your eyes are closed, most of your muscles are relaxed, and your consciousness is practically suspended. But while your body is still, your brain is quite active.

Sleep is important as it helps us restore and recover ourselves physically while also assisting us to organise things in our brain. People need sleep in order to function well – mentally and physically.

Going without sleep or having insufficient sleep can lead to a range of issues including:

• Poor mood / feelings of depression

• Lack of concentration

• Irritability

• Low motivation

• Heart disease

• Blood pressure

• Diabetes

• Increased likelihood of road accidents or workplace accidents

Sleep can be affected by a range of things including ageing, lifestyle commitments, injury, trauma, stressors, health problems, anxiety, depression, medication.

However a regular sleep pattern CAN be re-established after a disruption, even a significant disruption.

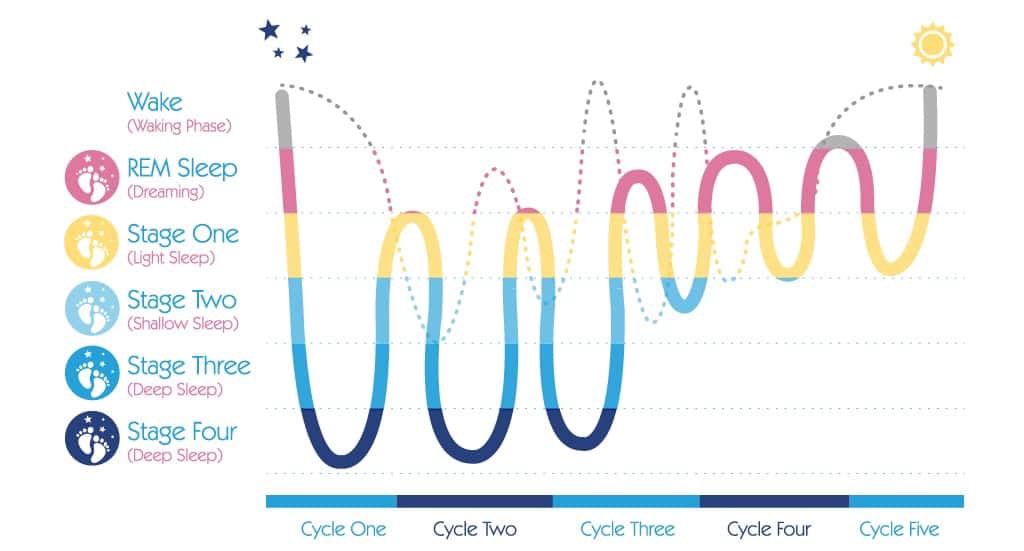

Sleep cycle

Sleep occurs in cycles that last around 90 minutes per cycle. During each cycle, different types of brain activity occur.

5 stages of sleep have been identified based on this brainwave activity:

Stage 1: Drowsiness. This is often referred to as the transition between awake and asleep. The eyes are generally closed, but the person awakens easily. If disrupted during this period, people will often state that they were not yet asleep or were just resting. This usually lasts for around 5-10 minutes

Stage 2: Light sleep. This sleep stage involves spontaneous periods of muscle activity mixed with periods of muscle relaxation. The heart rate slows and body temperature decreases. The body prepares to enter deep sleep.

Stages 3 and 4: Deep Sleep. Also known as slow-wave or delta sleep. During these stages the breathing is more relaxed, heart rate slows, sound and light sensitivity diminish. It is difficult to wake someone while in a deep sleep. Quality sleep needs to include deep sleep. Often when people seem to have had sufficient sleep (as measured by hours of sleep) but are still tired and fatigued each morning, it may be that they are not achieving deep sleep in their cycle. This deep sleep is vital in the secretion of the growth hormone. This hormone is necessary to restore the body and if this does not occur, people can be more prone to infections and disease. Alcohol, medication and stress can all impact on your ability to achieve deep sleep.

Stage 5: REM (Rapid Eye Movement) sleep. Also known as dream sleep. During REM sleep there is heightened brain activity, but the mind paralyses the muscles, possibly to keep the body from acting out the dreams and harming itself. The first period of REM typically lasts around 1 minutes, with each recurring REM stage becoming longer. The final stage may last around an hour. REM sleep is vital for normalising cognitive and emotional activities.

How much sleep do we need?

Different people require different amounts of sleep, which changes over a person’s life span. The average for an adult is around 7-8 hours, but anything within 5–10 hours can be normal.

The best guide to whether you are having enough sleep is how you function throughout the day. If you are sleepy and struggle to concentrate it is likely you are not getting enough sleep.

The first 3-5 hours of sleep is when the deepest sleep occurs (see graph above). This is the most restorative.

Waking up a few times during the night is quite normal and nothing to be concerned about. This usually occurs during the periods of light or REM sleep spaced out over the night. Being concerned or worried about waking up generally increases the likelihood of it being difficult to get back to sleep and increase these awake periods.

Sleep deprivation Scale

The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) can provide a measure of the impact of sleep deprivation on daytime function. This should only be used by people not on sleep medication.

If you feel you may be deprived of sleep and are not taking any sleep medication, completing this quick scale can give you an indication of how much impact it is having on your life:

0 would never doze

1 slight chance of dozing

2 moderate chance of dozing

3 high chance of dozing

Situation Rating

Sitting and reading ______

Watching TV ______

Sitting inactive in a public place (e.g. movie or meeting) ______

Passenger in a car for 1 hour with no break ______

Lying down in the afternoon when circumstances permit ______

Sitting and talking to someone ______

Sitting quietly after a lunch without alcohol ______

In a car, while stopped for a few minutes in traffic ______

TOTAL ______

Score indicator:

0-4 Satisfactory daytime functioning

5-9 Daytime tiredness, lack of energy

>10 Excessive daytime sleepiness

Sleep Diary

If you feel you have an issue with sleep or score 5 or above on the Epworth scale, the first step in making change can be to record relevant information in a sleep diary for 4-5 days in a row. This should give a clear indication of a baseline pattern and can identify potential problem areas and solutions.

Each day record:

• any daytime naps and their duration

• number of cups of tea, coffee, cola or energy drinks and approx. time each one was consumed

• number of standard drinks of alcohol and approx. time of consumption

• any sleep medication and time taken

• time when you go to bed

• approx. time when you fall asleep

• number of times you wake through the night and approx. indication of how long you were awake for

• time when you wake

• time when you got out of bed

It is important not to be too obsessed with clock watching or it will interfere with your natural pattern. This is particularly the case when waking in the night – clock watching will only increase the time you are awake for. An estimate of your sleep behaviours is fine.

Creating Positive Change

People who are having difficulties with sleep during the night often try to go to bed earlier or stay in bed longer to “catch up” on their sleep. This generally makes the problem worse, as more time is spent lying in bed awake. Often people feel anxious or frustrated about not sleeping during this time, which can build up an association between being in bed and negative emotions.

It is not necessarily easy to re-set your sleep pattern. It needs commitment and persistence. Initially you are likely to feel tired and irritable and may even get less sleep as your body adjusts to a new pattern. You will often feel more tired during the day, but it is important not to nap until the pattern is established.

Be aware it may take from 4-6 weeks to notice any improvement – repetition and consistency is key.

Effective Strategies:

• The most effective strategy when re-introducing a sleep pattern is ensuring a regular wake-up time. Stick to this wake-up time 7 days per week, even if you feel you haven’t had much sleep during the night.

• Get sunlight within 10-15 minutes of waking if possible.

• Only go to bed when you feel sleepy rather than at a fixed time in the evening.

• Establish a regular evening sleep routine – this is a pattern of behaviour that tells your body and mind it is time to go to sleep.

• Only stay in bed if you are sleeping. If you are lying in bed awake for more than 20 minutes, get up and do something relaxing in another room until you feel tired again.

• Only use the bed/bedroom for sleep or sexual intimacy. Avoid laying in the bed to rest during the day or using the bedroom to watch TV, eat, smoke, work, play computer games or chat on your phone.

• Avoid taking daytime naps.

During the Day:

• Keep a regular routine for meals, medication and general daily activities

• Pace your activities throughout your day

• Spend time outdoors in the afternoon if possible

• Avoid napping

• Keep as active as possible

• Reduce coffee to no more than 3 cups per day

During the evening:

• Relax and prepare for sleep

• Utilise an hour of quiet activity before you intend to sleep

• List what is on your mind and organise to do it tomorrow (to avoid worrying or planning throughout the night)

• Learn and use a relaxation tool to switch off. This may be a breathing exercise, mindfulness, meditation, or something that works for you.

• Avoid exercise late in the evening – light exercises early in the evening can be helpful

• Avoid caffeine for at least 5 hours before bedtime

• Avoid smoking before bedtime and during wakening

• Avoid alcohol near bedtime

• Avoid a heavy meal too close to bedtime

• Reduce disturbing noises and be calm about the unavoidable

• Avoid screentime – particularly laptops and mobile phones for one hour before bed

At bedtime:

• Develop a bedtime routine and follow it every night

• Recognise any emotional responses for what they are and use appropriate coping techniques to deal with such responses

• Only go to bed when you feel ‘sleepy tired’, not when you are just physically exhausted or you think its time for bed

• Keep reading and TV for another room

• Avoid using your bed for anything other than sleep or sexual intimacy

• Do not lie in bed awake for longer than 15-20 minutes

• During that 15-20 minutes enjoy relaxing in bed if you do not fall straight to sleep

• Use relaxation techniques to induce sleep

• Prepare somewhere to go (e.g. another room) and something to do if you do have to get up

• Return to bed only when you feel sleepy again

• Repeat the rising routine as frequently as necessary

• Keep the bedroom dark

When getting up in the morning:

• Get up at the same time each morning

• Have a routine that refreshes and takes your needs into account

• Allow time to avoid demanding morning routines

• Make a plan for the day

• Ensure that you have at least one rewarding activity.

Important tips when trying these strategies:

• Rather than being discouraged if there are lots of things you have identified that you can change, be pleased that you have identified a number of things that can help as this increases your chance for improvement.

• Don’t expect to have great results overnight – improvement may take 4-6 weeks.

• Change can take longer if the reasons for the sleep disruption are more complex. Be patient with yourself and take things one step at a time.

• It can be helpful in the initial stages to focus on behaviours/strategies you can ADD rather than things you need to avoid or stop doing.

• Feeling tired throughout this process of change is totally normal – feeling sleepy during the day is often one of the last things to disappear.

• A habit is learned and established by consistent repetition over long periods of time – it might be hard, but don’t give up!

SUMMARY: Tips to Sleep Better

• Stick to a consistent wake up time – even on the weekends. This helps to regulate your body’s clock and could help you fall asleep and stay asleep for the night.

• Practice a relaxing bedtime ritual. A relaxing routine activity right before bedtime conducted away from bright lights helps separate your sleep time from activities that can cause excitement, stress or anxiety.

• Avoid daytime naps – particularly in the afternoon. Power napping may help you get through the day, but if you find that you can’t fall asleep at bedtime, eliminating even short catnaps may help.

• Exercise daily. Vigorous exercise is best, but even light exercise is better than no activity. Exercise at any time of day, but it is best to avoid vigorous exercise for a few hours before bedtime.

• Avoid alcohol, caffeine, cigarettes and heavy meals in the evening. You may feel that alcohol or heavy meals make you tired enough to fall asleep, but these can interrupt with the natural sleep cycle and may lead to waking early or not getting sufficient deep sleep.

• Wind down – Your body needs time to shift into sleep mode, so spend the last hour before bed doing a calming activity such as reading, talking, or listening to music. For some people using an electronic device such as a laptop or phone can make I hard to fall asleep because the particular type of light coming from the screens is activating to the brain. If there are any activities that you associate with anxiety about sleeping, remove them from your bedtime routine.

• Evaluate your room. Design your sleep environment to establish the conditions you need for sleep. Your bedroom should be on the cooler side (around 15-19 degrees). It should also be free from any noise and light that can disturb your sleep. If you have environmental distractions you can’t remove, try using eye shades, ear plugs, white noise machines, or other devices.

• Sleep on a comfortable mattress and pillows – Make sure your mattress and pillow is comfortable and supportive.

• If you can’t sleep, don’t just lay there – go into another room and do something relaxing until you feel tired.

• Use your bed only for sleep and sex to strengthen the association between bed and sleep.

Our Rehabilitation Counsellors can help you to implement these strategies and improve your sleep health. Contact us today for more information if you need additional assistance.

Wednesday the 24th of July is Stress Down Day. Here are our tips for reducing stress!

#1 Identify symptoms and causes of stress

In order to reduce stress, we first must be aware of the symptoms of stress and also identify the causes. Signs of stress vary from person to person, but may include tensing your jaw, grinding your teeth, difficulty sleeping, muscle tension, headaches, feeling irritable or short tempered, lack of concentration or motivation, feeling overwhelmed, depressed or anxious, and overuse of alcohol or drugs as a coping mechanism. Sometimes it can be difficult to identify the cause of stress and there are often multiple factors involved, so keeping a journal to track your stressors may be useful. Clearly identifying what is causing the stress is the first step in doing something about it. Sometimes the cause of stress can be eliminated, and at other times it is about developing more effective coping mechanisms.

#2 Use problem-solving to eliminate the cause of stress

Once you have determined the cause of stress, some stressful situations can be eliminated, reduced or changed by problem solving. It is often helpful to write down a list of possible solutions, work through the pros and cons of each, select the best one, try it out and evaluate its success. Focus on the things that are within your control. If you have multiple stressors it is generally best to focus on one at a time.

#3 Organise and manage your time effectively

Research suggests that good time management can decrease stress, increase satisfaction with work and life and generally improve health. Some strategies to improve your time management include setting goals, prioritising tasks, using a diary or to-do lists to track tasks and progress and delegating work to others. It is important to accept that not everything can be done at once and list tasks according to genuine priority. Being organised can also be as simple as sorting out your morning routine to avoid rushing or tidying up your work area for a calmer and more productive work day.

#4 Practise relaxation techniques

Practising relaxation techniques regularly has been found to reduce stress. This can include a range of activities such as: meditation, breathing exercises, progressive muscle relaxation or mindfulness. These techniques can help reduce stress levels by allowing the body and nervous system to settle into a calm state. They don’t need to take long, just one minute of focus on breathing or mindful noticing of the tangible things you can experience with your 5 senses can help if practised regularly. Different methods will be effective for different people – you might have to try a few approaches before you find something that works for you. There are lots of apps available that can help you add some relaxation techniques to your busy lifestyle. Structured activities such as Yoga, Pilates can be beneficial too!

#5 Look after your health

Stress can affect your immune system and make you more vulnerable to a range of health conditions. Keeping yourself fit and healthy can improve your resilience and enable you to cope more effectively with stressful situations.

🥗 Eat a healthy and well balanced diet

🥛 Drink plenty of water

🚫 Avoid or reduce consumption of alcohol, caffeine, nicotine and other drugs, especially if you are overusing these to cope

❌ Avoid or reduce intake of refined sugars as they can cause energy crashes and lead you to feel tired and irritable

🏌️♀️Ensure you get some physical activity each day and exercise regularly

#6 Increase Daily Physical Activity

Stressful situations increase the level of stress hormones such as adrenaline and cortisol in your body. These are the “fight or flight” hormones designed to protect us from bodily harm when we are under threat. However it is unlikely that your stressful situation will require a physical fight or flight response and so physical exercise can be used to metabolize the excess stress hormones and restore your body to a calm and relaxed state. 🧘🏾♀️

Additionally, regular physical exercise is good for your general health and well-being and can keep you feeling positive and more able to cope with stressful situations when they arise. Simple changes to your daily routine such as going for a 30 minute walk during your lunch break or kicking the footy with your kids after work can make a BIG difference!!

#7 Ensure you are getting enough sleep

A lack of sleep is a significant cause of stress, however it can also be a symptom of stress as thoughts whirling around your head can make it difficult to fall asleep. If sleep is an issue for you, it can help to create a relaxing evening routine that gets you prepared and ready for sleep and aim to go to bed at the same time each night so your mind and body can get into a good sleep pattern. Avoid caffeine and excessive alcohol in the evenings as these can lead to disturbed sleep patterns. Don’t engage in mentally engaging activities for a few hours before bedtime to allow your brain time to calm down. Turning off screens (TV, smartphones, laptops) at least one hour before bed can also help. Some helpful activities to do before bedtime include some light reading, talking quietly with the lights dimmed, or taking a warm shower or bath.

#8 Rest if you are unwell

Often we can be guilty of putting too much pressure on ourselves, and contributing to our own stress. A good example of this is feeling like we have to carry on, even when we are unwell. A short rest can often help the body to recharge and recover from illness. Whether this means taking a day off work when you are sick, or simply letting some of your other responsibilities (such as housework) go for a short time while you recover. Looking after yourself is very important!!

#9 Learn to say no

A common cause of stress is having too much to do and too little time to complete it. And yet, in this predicament so many of us still agree to take on additional responsibility when asked. Learning to say “no” to additional or unimportant requests can assist in reducing stress and may even lead to an increase in confidence and self-esteem.

To learn to say “no” requires an understanding of why you find it difficult. Many people find it hard to say “no” because they want to help and are trying to be nice and be liked. For others it can be a fear of rejection or missed opportunities. Understanding what drives you can assist you in taking control and ensuring that you are placing as much importance on your own time and health as you do for others.

#10 Make time for things you enjoy

Take your mind off your worries by ensuring you allow plenty of time for enjoyable activities. This may feel impossible if you are overwhelmed with too much to do, however taking a bit of time out for yourself to do something positive or fun may ultimately lead to better coping skills and increased productivity. Ideas may include gardening, listening to music, socialising, going to the gym, getting into nature, reading, taking a bubble bath… the list is endless! What is your favourite enjoyable activity that you find helps to alleviate stress?

#11 Create a healthy work-life balance

Work plays a very big role in our lives, but it’s important to balance this with other life activities. If work is increasing your stress levels, think about other areas of your life that you would like to focus on (eg. Relationships, exercise, recreation, social activities) and how you can also prioritise these aspects in your daily life.

Taking time to wind down and enjoy relaxing activities is an important part of balanced life and helps to reduce stress. Include relaxing as well as uplifting activities into your daily or weekly routine.

#12 Stay away from conflict. Resolve issues when they arise.

Interpersonal conflict takes a toll on our physical and emotional health. Its a good idea to avoid conflict at work and in your personal life as much as possible. Surround yourself with positive people that make you feel good about yourself as much as you can. Avoid gossip or discussing volatile topics (such as religion or politics) at work. If conflict finds you anyway, learn positive ways to deal with it and ask for support if you need to.

#13 Resist perfectionism

Mistakes shouldn’t be feared – they are an opportunity to learn and improve! The desire to be perfect can make your stress spike and your self-worth plummet. Recognise that you are not defined by your failures, instead see them as an opportunity for improvement and self-discovery. Remember no one is perfect – and people who may appear that way on the outside may be struggling with their own unrealistic perfectionistic standards.

#14 Practise positive self-talk

When we are stressed we often say negative or self-defeating things to ourselves over and over. Unhelpful self-talk may include things like “I can’t cope”, “I’m too busy to deal with all of this”, “I’ll never get this done” or even “I’m completely useless”. Notice this self talk and think about more constructive ways to talk to yourself. Practise saying positive statements to yourself, ensuring they are realistic and that you believe them. Suggestions could be “I am coping well given what I have on my plate at the moment”, or “This is tough at the moment but I know I’ll get through it and things will be easier on the other side”.

Try and keep things in perspective – when we are stressed it is easy to catastrophise and see things as far worse than they really are. Ask yourself “how likely is it that that negative event will happen?” or “am I overestimating how bad the consequences will be?”

#15 Talk to someone

Its okay to need support sometimes. Don’t be afraid to admit when you need help to enable you to cope. There are a range of people you can talk to when you are feeling stressed, for example, family members, co-workers, supervisors, bosses, doctors or psychologists. Your employer may have stress management resources available or your doctor may be able to refer you to a psychologist or mental health professional. If you are feeling overwhelmed it is a good idea to ask for support, especially if it is prolonged over a period of time.

In order to combat unhelpful thinking styles you must learn to leave your negative thoughts behind. The trick is not just to stop the ongoing storm of thoughts, but rather to change the nature of the thoughts from destructive to positive and life-enhancing ones.

As you commit yourself to eliminating these negative ways of thinking, you must understand two factors. First, these unhelpful thinking patterns are much more likely to emerge when you are fatigued or highly stressed,or when there is a significant problem facing you. These situations weaken your ability to cope and contribute to distorted thinking. Ironically, these bad thinking habits emerge when there’s a problem, and that’s exactly when effective coping responses are needed most. When things are going reasonably well, they may not be apparent at all.

Also, many people do not experience these thought disorders with all problems. These habits instead tend to emerge when a problem touches on an area of personal vulnerability or emotional sensitivity. By noticing exactly when distorted patterns emerge, you can pinpoint unresolved personal conflicts, thereby enhancing your personal awareness. These emotional “soft spots” clearly call for strengthened coping skills.

How do you get rid of these self-defeating ways of thinking?

It can be done, but will require self-awareness, patience, practice and support.

Here are some helpful hints:

- Verbalise your thoughts when a problem occurs.

To build awareness of distorted thinking, think out loud when you have a problem. You may even need to record yourself and play it back. If you have a trusted friend you could run your thoughts past them to see how they sound when said aloud to another person. You may be very surprised at how negative and self-defeating your thoughts actually are. Remember that these thoughts reinforce negative perceptions of you and reality.

- Do not project thoughts onto other people.

It’s easy to attribute unfairly negative thoughts to loved ones or close friends. To eliminate distorted thinking, first take full responsibility for your thoughts. Then open yourself to give other people a chance to care about you.

- Work on one habit at a time.

Most people are prone to several different negative thought patterns. To tackle them all at once is usually self-defeating. Instead, identify one distorted thinking habit and work on that one alone until it is eliminated. Then move onto another one until you overcome all of them.

- Act as if you are completely competent and in control (Fake it until you make it!)

In the beginning, force yourself to do this in lieu of negative thinking in order to give new ways of relating to a problem a chance. You will feel better because problems don’t seem so overwhelming, and you are coping more effectively. “What you say to yourself, you become.”

- Use thought-stopping as a technique.

When you find yourself slipping into distorted thinking, internally shout to yourself, “STOP!”

STOP -> THINK –> Then TALK/ACT

- Practice positive affirmations.

Even when you feel good, it’s helpful to make self-reinforcing statements. However, these need to be realistic and practical. Saying “everything will be wonderful in the end” may not be helpful, because sometimes things do not turn out this way. However, saying “No matter what obstacles are thrown at me, I am strong enough to overcome them” is quite different. Whether you initially believe it or not, practising saying it aloud will reinforce those beliefs and you will start to believe them. No matter where you are, keep your self-affirming thoughts going.

- Put positive suggestions by others into practice.

It is often helpful to ask for and really listen to feedback from your partner or a good friend. When you do, make it a point not become defensive, because receiving feedback often triggers negative thinking. You may find yourself gaining insight into how to cope more effectively.

- Separate yourself from negatively thinking peers.

Often negative perceptions are reinforced by friends, especially when discussing personal or relationship struggles. If you need to talk it out, find one upbeat friend who is helpful to use as a sounding board.

Bottom line: It’s very difficult, if not impossible, to live life happily when you feel insecure, unloved, distrustful of others, and threatened by events around you. But most of these feelings you create yourself. You can’t change the world, but you can change yourself and the way you perceive life events.

You don’t need special skills to support someone in need. Asking, “Are you OK?” with kindness, concern and in a genuine way can make a world of difference. A day to help to inspire and empower everyone to meaningfully connect with people around them and support anyone struggling with life.

In 1995, much-loved Barry Larkin was far from ok. His suicide left family and friends in deep grief and with endless questions.

In 2009, his son Gavin Larkin chose to champion just one question to honour his father and to try and protect other families from the pain his endured.

“Are you OK?”

The extraordinary story behind R U OK? was brought to life by Australian Story in 2011.

We know that suicide prevention is an enormously complex and sensitive challenge the world over. But we also know that some of the world’s smartest people have been working tirelessly and developed credible theories that suggest there’s power in that simplest of questions – “Are you ok?”

One of the most significant theories is by United States academic, Dr Thomas Joiner. 1 Because his father took his own life, Thomas has dedicated his research to try and answer that question “why?”

His theory tries to answer that complex question by describing three forces at play in someone at risk. The first force is the person thinks they’re a burden on others; the second is that they can withstand a high degree of pain; and the third is they don’t feel connected to others.

It’s this lack of connection (or lack of belonging) that we want to prevent. By inspiring people to take the time to ask “Are you ok?” and listen, we can help people struggling with life feel connected long before they even think about suicide. It all comes down to regular, face-to-face, meaningful conversations about life. And asking “Are you ok?” is a great place to start.

As well as helping you start these conversations, we’re working with experts in the field to monitor how these conversations impact on Australia’s suicide rate.

HOW TO ASK:

By starting a conversation and commenting on the changes you’ve noticed, you could help that family member, friend or workmate open up. If they say they are not ok, you can follow our conversation steps to show them they’re supported and help them find strategies to better manage the load. If they are ok, that person will know you’re someone who cares enough to ask.

For more information or to Donate to support such a meaningful fund please visit:

Counselling (24/7)

If you need further support please contact one of the following numbers

• Lifeline Australia – 13 11 14

• Lifeline New Zealand – 0800 543 354

• Kids Helpline – 1800 55 1800

• MensLine Australia – 1300 78 99 78

• Suicide Call Back Service – 1300 659 467

• Beyond Blue – 1300 22 4636

• Veterans and Veterans’ Families Counselling Service – 1800 011 046

Beliefs and Definitions of pain

Historically, humans have been very interested in the pain experience and have had a wide variety of explanations regarding pain.

In Ancient Greece 500 BC they believed that pain occurred when the Goddess of revenge, “Poine” was sent to punish fools who had angered the gods. Treating pain involved prayer and animal sacrifice.

Many ancient cultures believed that pain was something inside the person which had become stuck and needed removal.

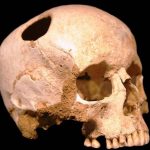

Holes were drilled into body parts and sometimes pipes were used to “suck the pain out”.

During the 1600s there were giant leaps in scientific understanding.

Rene Descartes proposed the idea that pain was a mechanical sensation transmitted to the brain. The body part that had been injured sent a message up to the brain where it could be received and understood as pain. In order to treat the pain either the injured body part needed to be fixed or the message needed to be stopped.

We have largely held onto this understanding of pain into current times. We only need to watch advertisements for commonly used painkillers to see images involving pain being transmitted from the injury to the brain and then the painkiller smashing away the transmission to stop the message before getting to the brain. Research has clearly shown that pain is far more complicated than this, through studies of people with phantom limb pain after amputation and a variety of other examples that clearly demonstrate that pain actually does not correlate well with degree of injury.

So what then is pain? There have been many attempts at defining pain.

Some of the more useful ones include:

“Pain is whatever the person in pain says it is.” – McCafferey (a nurse) 1968

“Pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage.” – The International Association for the Study of Pain (1994) and the World Health Organisation (2007)

“Pain is a construction in the brain to help us deal with threat, either real or perceived via a change in behaviour.” – Mature organism Model, Gifford (1998)

“Pain is a multiple system output activated by an individual specific pain neurosignature; the neurosignature is activated whenever the brain concludes that the body tissues are in danger and action is required.” – Lorimer Moseley (2003)

These more recent explanations of pain focus on threat and danger; pain is explained as a mechanism produced by the brain to protect us from harm. Physical harm (e.g. accidentally putting your hand onto the hotplate) is reasonably easy to understand. The combination of nociception (the activation of physical receptors to physical changes such as pressure, temperature and chemical change) as well as the visual perception of danger causes the brain to produce a pain response. This causes the physical response of quickly moving your hand away from the hotplate and perhaps running it under cold water. The pain response is not only caused by the physical stimulus of heat, but also by our awareness that leaving our hand on the hotplate could potentially lead to a severe burn (that is, our perception that the situation is potentially dangerous).

However, pain can occur in a variety of situations where there is no physical damage.

One example of this was documented in the British Medical journal in 1995. A builder jumped down onto a nail in a building site, which went right through his foot and was sticking out through the top of his shoe. Understandably, the man was screaming in considerable pain. He would not allow anyone to remove his shoe as the slightest movement caused extreme pain. He required sedation and strong pain medication to enable him to be x-rayed (with the shoe still on), to discover that the nail had actually gone straight between his toes and had not penetrated his foot at all – not even a scratch!

It may be easy to think that this pain is somehow not “real” as there was no damage. However, his pain is equally as real as if the nail had indeed gone right through his foot. In this case the visual perception, combined with previous experience involving serious injuries on the worksite was enough to cause the brain to decide the situation was extremely dangerous and that pain was required to ensure the danger could be resolved.

In other examples, people have had horrendous injuries and not experienced much, if any pain.

In 2010 Jonathan Metz had been trapped in his basement for approximately three days with his arm stuck in the furnace and little chance of being found chose to saw off his own arm in order to escape, and survive. After the traumatic incident explained his surprise at not experiencing much, if any pain through the process. He certainly expected it to hurt and felt physically sick looking at what he was doing, however only mild pain was felt. This can easily be explained through this threat model of pain, as his brain had come to the conclusion that the threat of being locked in the basement was far more dangerous than the threat of cutting off his arm. In the absence of a perception of danger involved, no pain needed to be produced. There are many similar examples in the area of sport, where athletes feel little or no pain during or immediately after a severe physical injury.

Important things we now know about pain

- No scan or test can tell if someone is feeling pain or not. X-rays, CT scans and MRI results have been consistently demonstrated to be very poorly correlated with the experience of pain.

- No one else can feel your pain

- ALL pain is real

- You cannot imagine pain

- Pain can be weird (e.g. delayed pain, phantom limb pain, pain that spreads to unrelated areas)

- Nociceptive nerve fibres are triggered by chemical change (e.g. inflammation), physical events (e.g. pressure), and temperature changes

- Nociceptive nerve fibres can adapt and amplify their signals through frequent triggering, generally leading to increased pain with reduced activity levels

- Pain is influenced (positively and negatively) by mood, concerns, thoughts, perception of control, importance placed on the injury, and a range of other cognitions.

- Pain can be influenced by boom/bust behaviour and flare ups

So what does this all mean?

Pain is useful and should not be ignored. Pain is a protective mechanism generated by the brain in response to perceived threat. However, when pain is persistent and there is no direct or immediate threat to the body, understanding how the body can get “stuck” in pain can suggest ways to help it get “unstuck.”

All current evidence leads to the conclusion that PAIN IS CHANGEABLE!

Pain is produced by the brain and we also know that the brain is constantly going through changes. Neuroplasticity can be defined as the brain’s ability to reorganise itself by forming new neural connections throughout life. Neuroplasticity allows the neurons (nerve cells) in the brain to compensate for injury and disease and to adjust their activities in response to new situations or to changes in their environment. Examples of this include learning a new skill, developing a taste for certain types of food and recovering from stroke. Dr Norman Doidge, A psychiatrist and researcher from the University of Toronto in Canada has highlighted the importance of neuroplasticity for healing a range of conditions from long term pain to Parkinson’s disease in his bestseller The Brain That Changes Itself (2007).

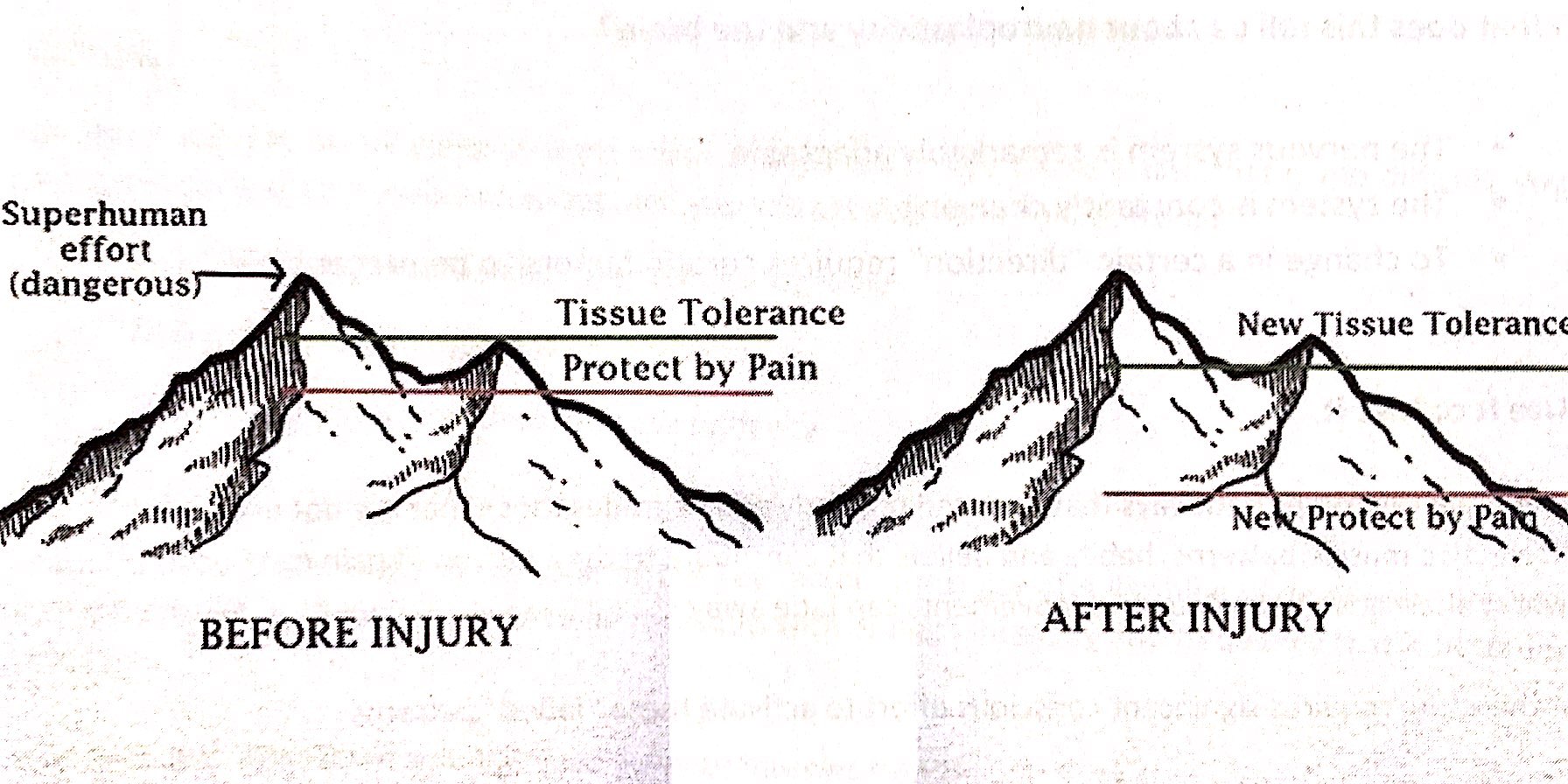

Everyone has a tissue tolerance level, that is a threshold where activities go from being safe to being dangerous. This differs between individuals and can also change over time through inactivity, exercise, strength training etc. When pain is working effectively, the protect by pain line sits under the tissue tolerance level so that as we begin to approach our tissue tolerance threshold, pain kicks in to remind us to stop or slow down or at least let us know we are reaching our limits. After an injury, the tissue tolerance level may slightly reduce as newly healed structures may not be quite as strong or capable as before. Most healing will be complete after 6 weeks (often much sooner, depending on the injury) meaning it is safe to go back to physical activity. However, in persistent pain problems, the protect by pain level has significantly dropped, so that even the slightest activity can be enough to set off the pain signal.

The key point to focus on is that these changes have primarily happened within the brain and the brain can be retrained. This retraining allows the protect by pain line to slowly and steadily increase until it is once again sitting just under the new tissue tolerance line. This is done through pain education and gradual exposure to safe activities through a pacing program. It is important that people know that even though it may hurt, the activity is safe. Building up slowly increases confidence and decreases the fear and threat of danger. The new tissue tolerance line can also be changed through safe exercise and strengthening activities. People do not have to suffer ongoing pain indefinitely.

At Adaptive Workplace Solutions we can provide pain education combined with meaningful goal setting and pacing/graded exposure plans to assist people with ongoing pain problems get back to everyday activities for work, play and life! If you would like further information please contact us to talk to one of our consultants in more detail. For further reading, we highly recommend the book Explain Pain by Dr David Butler and Dr Lorimer Moseley.

In the Position Statement ‘What is Good Work?’ (2013) written by the Australasian Faculty of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (AFOEM*) of The Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP), it is stressed that not all work has a beneficial impact on health. They detail 5 key domains of good work, but also highlight individual differences and the importance of a good fit between the individual and the work tasks and environment. What is beneficial for one person may be harmful for another. In order to reap the health, social and economic benefits of work, it is essential for governments, regulators, insurers, business leaders and employers to focus on what constitutes “good work” while also ensuring a good match between the individual and the role.

According to AFOEM’s ‘Consensus Statement on the Health Benefits of Good Work’ (2017), good work:

• is engaging, fair and respectful

• balances job demands, autonomy and job security

• accepts the importance of culture and traditional beliefs

• is characterised by safe and healthy work practices

• strikes a balance between the interests of individuals, employers and society

• requires effective change management and clear and realistic performance indicators

• matches the work to the individual

• uses transparent productivity metrics.

Under this definition of good work, they acknowledge the following principles:

• The provision of good work is a key determinant of the health and wellbeing of employees, their families and broader society.

• Long term work absence, work disability and unemployment may have a negative impact on health and wellbeing.

• All workplaces should strive to be both healthy and safe.

• Providing access to good work is an effective means of reducing poverty and social exclusion.

• With active assistance, many of those who have the potential to work, but are not currently working, can be enabled to access the benefits of good work.

• Safe and healthy work practices, understanding and accommodating cultural and social beliefs, a healthy workplace culture, effective and equitable injury management programs and positive relationships within workplaces are key determinants of individual health, wellbeing, engagement and productivity.

• Good outcomes are more likely when individuals understand, and are supported to access the benefits of good work especially when entering the workforce for the first time, seeking re-employment or recovering at work following a period of injury or illness.

For more detail and information please refer to the following references.

References:

Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP) Website – Health Benefits of Good Work

‘Realising the Health Benefits of Good Work Consensus Statement’ (2017) Australasian Faculty of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (AFOEM)

‘What is Good Work?’ (2013) Australasian Faculty of Occupational and Environmental Medicine

Return to Work SA Health Benefits of Work Fact Sheet

The general health benefits of daily walking have been widely documented and include healthy weight maintenance, improved heart health, improved sleep patterns, reduced stress and boosting mood. These benefits are even more pronounced when recovering from a workplace injury.

One of the biggest barriers workers often face after an injury is a loss of physical fitness and a general decrease in activity levels. Many injured workers report withdrawing from a variety of activities they previously enjoyed, leading to a variety of health issues in addition to their original injury.

Walking is an activity that is widely accessible to most people who have suffered an injury and can be easily adjusted to compensate for a variety of restrictions.

Exposure to sunshine adds the extra benefit of boosting Vitamin D levels which have found to be deficient in around 30% of Australians. Vitamin D supports bone health by regulating calcium levels in the blood and maintaining a healthy skeleton.

Walking also positively effects mental health with benefits including clearing the mind, increasing general energy levels, reducing symptoms of depression and boosting self-esteem.

Embarking on a 30 minute walk every day has even been related to an increase in natural pain killing endorphins.

So what are you waiting for? Start a walking program today!